visualisation by E.Rakhimberdiev

visualisation by E.Rakhimberdiev

Population ecology and conservation of migratory birds

Every year migratory birds travel Earth ecosystems in a pursuit of seasonal peaks of resources. Separated by thousands of kilometres and exposed to various climatic and anthropogenic disturbances, these ecosystems change in different ways and at diverse rates. It is most intriguing to me how the long-distance migrants fit their annual routines to these nonaligned trends they encounter running through their annual routine.

I took a deeper look into the ways migratory bird populations respond to the variation in conditions along the flyways. For this, I have applied a mixture of - often self-developed - analytical techniques, and integrated numerous demographic (capture-resight) and other data on birds’ biology with Earth-observation datasets. My main discovery is that (1) in stable avian populations, selection pressure is evenly distributed throughout the annual cycle and (2) seeking to achieve stability, the populations dissolve elevated selection pressures that arise during specific stages in the annual cycle by taking on higher fitness costs at other stages.

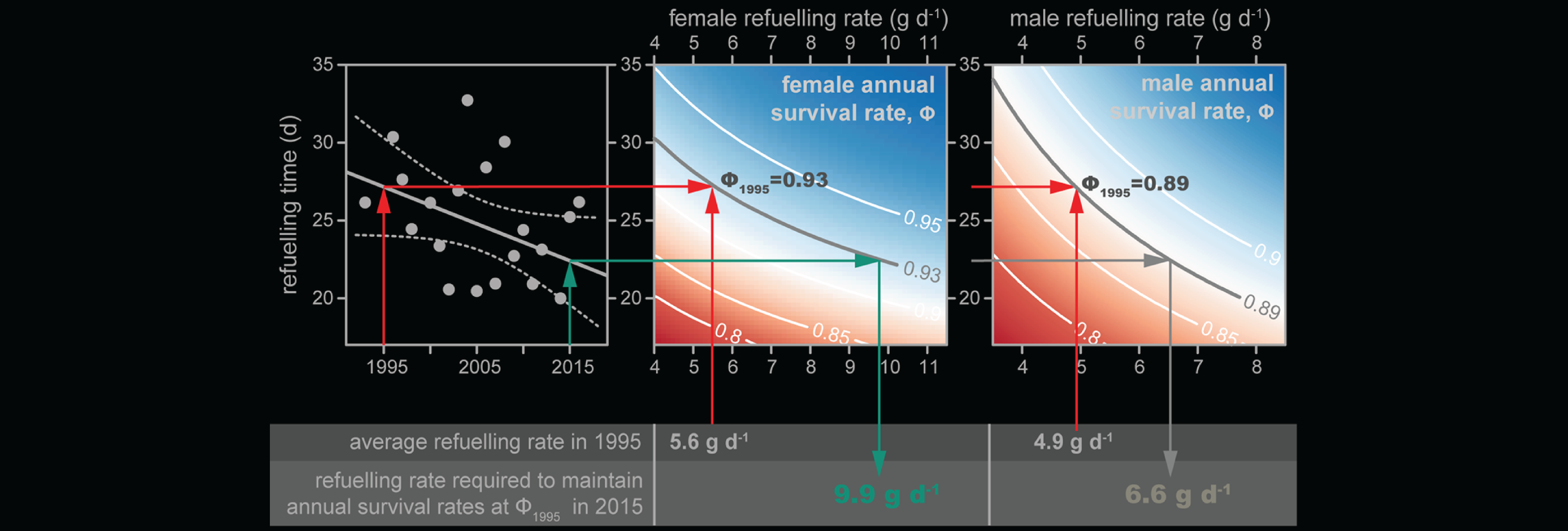

In Rakhimberdiev et al. 2016, J. Avian Biol. I use red knot Calidris canutus as an example to present my insight that deviation of mortality rates from baseline values anywhere in the annual cycle is a sign of maladaptation. I explore specific cases of rapid adaptation of annual routines in several migratory avian species: the ruff Philomachus pugnax (Rakhimberdiev et al. 2011, Div. Distr.), North American barn swallow Hirundo rustica (Winkler et al. 2017, Cur. Biol.) and the bar-tailed godwit Limosa lapponica (Rakhimberdiev et al. 2018, Nat. Comms). The latter publication demonstrates the mechanisms of fitness-cost redistribution from the breeding season to the earlier annual-cycle stages. However, redistribution of costs is limited, when selection pressure irreversibly carries over from the early developmental stages to adulthood (van Gils et al. 2016, Science).

The Dutch population of black-tailed godwits (Limosa limosa limosa) is going down, and the reason for the decline appears to be high level of nesting failure and brood mortality caused by intensification of agricultural practices. Currently I develop integrated population models to improve conservation of this species. Together with PhD student Marie Stessens and postdoc Dr. Rienk Fokkema I combine large and diverse datasets (including capture-resight of adults and juveniles, nest monitoring, chick radio-tracking and count data) within a spatially explicit model to determine the best agricultural practices for conservation of black-tailed godwits in the Netherlands.

In capture-recapture data collected within the project, I have discovered strong bias in estimates of survival probability arising from erroneous identification of individuals. I solve this problem by introducing a new class of robust design capture-resight models, accounting for misidentification (Rakhimberdiev et al., in revision, Methods Ecol. Evol.). Unbiased estimates delivered by these models are of critical importance for robust prognosis of population dynamics in animal conservation.